Paris bus sign: “Jean-Luc has a name”

“Jean-Luc has a name. So it’s not worth it calling him names. Thank you for speaking to the bus driver and to other passengers with courtesy. Let’s share more. Let’s share the bus.”

—RATP [Paris public transport sysem] in its new politeness campaign on the Paris buses

Little girl named after cheese dish

A little girl in Belgium is named Lara Clette (la raclette is a cheese dish from the Alps) and the parents didn’t even notice until, the father told a reporter, “my father-in-law came to the hospital and said, ‘I thought you liked fondue better than raclette’…”

Nous n’avons jamais pensé à l’association du prénom avec mon nom. Ce n’est que lorsque mon beau-père est venu à la maternité et qu’il m’a dit: “ je croyais que tu préférais la fondue à la raclette ” que nous avons fait “ tilt ”. On a pensé changer le prénom dans les trois jours mais les infirmières nous ont dit qu’il était joli. Nous aussi, on l’aimait beaucoup….

Lyle Saxon on Cajun names, circa 1945

Curious names are popular along the bayous. Some that graced heroic characters of Greece are hereditary among the Cajuns. Hundreds of males titled Achille, Ulysse, Alcide and Télémaque now row pirogues through Louisiana waterways. There is a penchant for nicknames. Even animals have them. Every cat is “Minou,” and every child is given some diminutive of his name. It is perfectly safe to say that no group of Cajuns ever assembled without a Doucette, a Bébé, a Bootsy or a Tooti among them. At one school a family of seven children, named Thérèse, Marie, Odette, Lionel, Sebastian, Raoul, and Laurie, were known even to their teachers as Ti-ti, Rie, Dette, Tank, Bos, Mannie and La-la. It is said that every Cajun family has a member known as “Coon.” Other families, like the Polites, give their offspring names that all start with the same letter. An “E” family might be, respectively, Ernest, Eugénie, Euphémie, Enzie, Earl, Elfert, Eulalie and Eupholyte.

However, there are comparatively few family names. There are literally thousands of Landrys, Broussards, Leblancs, Bourgeoises and Breaux, these being the largest families of Acadian descent in the state.

—Lyle Saxon (1891-1946) in Gumbo Ya-Ya (pub. 1945)

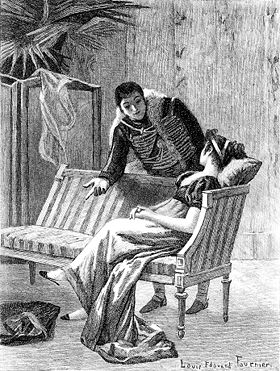

Jacques Prévert: Odd, to ask people who they really are

Don’t you find that it’s an odd question, to ask people who they are? … They go for the easy answer: their last names, their first names, their positions, but who are they really? They keep it to themselves deep down inside, they carefully hide it.

—The poetic criminal Lacenaire (based on a real person) in Les Enfants de paradis (1945). The script was written by Jacques Prévert

Vous ne trouvez pas que c’est une question saugrenue que de demander aux gens qui ils sont ?… Ils vont au plus facile : nom, prénoms, qualités, mais ce qu’ils sont réellement ? Au fond d’eux-mêmes, ils le taisent, ils le cachent soigneusement.

Balzac’s names

advanced into his work, the less he invented or deformed the names he used. Thus the beauty of the Balzacien name comes essentially from the weight it has on human beings, who can never change it, even when they try, like bastards, criminals, or great ladies wishing for a new personality. The bourgeois name is a true tunic of Nessus, which one never manages to completely rip off, especially in the modern French onomastic system, infinitely more binding than the practice of the Ancien Régime, entirely commanded by the father’s name. It is the sign of a civilization of writing. And everyone is obsessed with the desire for an indelible signature, in inscribing his name in the commercial, scientific, historical, or institutional circuit. The bourgeoisie of the 19th century gave itself up to a veritable onomastic debauchery, in “giving” its names to anything and everything, to a product, to streets, to discoveries, mountains, or literary prizes. When Balzac delved with both hands into the names of his neighbors in Tours for his characters’ names, all he did was anticipate this way of behaving. The procedure is the same for places: to take their names is to symbolically appropriate their substance, the best of their being.

advanced into his work, the less he invented or deformed the names he used. Thus the beauty of the Balzacien name comes essentially from the weight it has on human beings, who can never change it, even when they try, like bastards, criminals, or great ladies wishing for a new personality. The bourgeois name is a true tunic of Nessus, which one never manages to completely rip off, especially in the modern French onomastic system, infinitely more binding than the practice of the Ancien Régime, entirely commanded by the father’s name. It is the sign of a civilization of writing. And everyone is obsessed with the desire for an indelible signature, in inscribing his name in the commercial, scientific, historical, or institutional circuit. The bourgeoisie of the 19th century gave itself up to a veritable onomastic debauchery, in “giving” its names to anything and everything, to a product, to streets, to discoveries, mountains, or literary prizes. When Balzac delved with both hands into the names of his neighbors in Tours for his characters’ names, all he did was anticipate this way of behaving. The procedure is the same for places: to take their names is to symbolically appropriate their substance, the best of their being.—Nicole Mozet, La ville de province dans l’oeuvre de Balzac: l’espace romanesque : fantasme et ideologie (Paris, Societe d’edition d’enseignement superieur, 1982)

La Comédie humaine est une enorme épopée onomastique. Les noms propres sont des morceaux de corps, des morceaux de terre, de purs signifiants. Dans tout son oeuvre, Balzac nous présent des noms magiques, comme celui de Foedora ou de Z. Marcas, des noms prestigieux, comme celui de Beauséant, des noms drolatiques, comme Beaupertuys, des noms grossiers, comme Beauvisage, voire ignobles, comme Crochard ou Gaubertin….

…cette “singulière theorie sur les noms” que professait Balzac, d’après sa soeur, et qui voulait que “les noms inventés ne donnent pas la vie aux êtres imaginaires, tandis que ceux qui ont réellement été portés les douent de réalité.” Il semble effectivement que Balzac, au fur et à mesure qu’il s’avançait dans son oeuvre, ait de moins en moins inventé et déformé les noms qui’il utilisait. Aussi la beauté du nom Balzacien vient-elle essentiellement du poids que celui-ci fait peser sur les êtres, qui n’en peuvent jamais changer, même quand ils essaient, comme les bâtards, les criminels, ou les grandes dames en mal d’une nouvelle personnalité. Le nom bourgeois est un véritable tunique de Nessus, que l’on ne parvient jamais à arracher complètement, surtout dans le système onomastique français moderne, infiniment plus contraignant que la pratique de l’Ancien Régime, et entièrement commandé par le nom du père. C’est le signe d’une civilisation de l’écrit. Et chacun d’être obsédé par le désir d’une signature indélébile, en inscrivant son nom dans le circuit commercial, scientifique, historique ou institutionnel. La bourgeoisie du XIXeme siècle s’est livrée a une véritable débauche onomastique, en “donnant” ses noms à tous vents, à un produit, à des rues, à des découvertes, à des montagnes ou à des prix littéraires. Balzac n’a fait qu’anticiper sur cette façon d’agir lorsqu’il a puisé à pleines mains dans les noms de ses voisins de Tours pour les faire porter par ses personnages. Le procédé est le même quand il s’agit des lieux: prendre leurs noms, c’est s’approprier symboliquement leur substance, le meilleur de leur être.

…cette “singulière theorie sur les noms” que professait Balzac, d’après sa soeur, et qui voulait que “les noms inventés ne donnent pas la vie aux êtres imaginaires, tandis que ceux qui ont réellement été portés les douent de réalité.” Il semble effectivement que Balzac, au fur et à mesure qu’il s’avançait dans son oeuvre, ait de moins en moins inventé et déformé les noms qui’il utilisait. Aussi la beauté du nom Balzacien vient-elle essentiellement du poids que celui-ci fait peser sur les êtres, qui n’en peuvent jamais changer, même quand ils essaient, comme les bâtards, les criminels, ou les grandes dames en mal d’une nouvelle personnalité. Le nom bourgeois est un véritable tunique de Nessus, que l’on ne parvient jamais à arracher complètement, surtout dans le système onomastique français moderne, infiniment plus contraignant que la pratique de l’Ancien Régime, et entièrement commandé par le nom du père. C’est le signe d’une civilisation de l’écrit. Et chacun d’être obsédé par le désir d’une signature indélébile, en inscrivant son nom dans le circuit commercial, scientifique, historique ou institutionnel. La bourgeoisie du XIXeme siècle s’est livrée a une véritable débauche onomastique, en “donnant” ses noms à tous vents, à un produit, à des rues, à des découvertes, à des montagnes ou à des prix littéraires. Balzac n’a fait qu’anticiper sur cette façon d’agir lorsqu’il a puisé à pleines mains dans les noms de ses voisins de Tours pour les faire porter par ses personnages. Le procédé est le même quand il s’agit des lieux: prendre leurs noms, c’est s’approprier symboliquement leur substance, le meilleur de leur être.