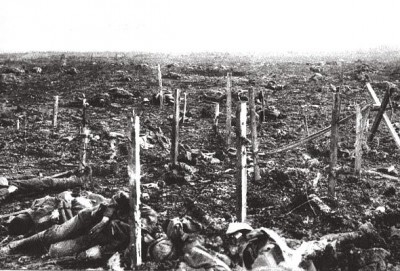

—Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), A Farewell to Arms (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929), p. 191. The speaker is the narrator, Frederick Henry.

Blood and Gore

Former U.S. Vice-President Al Gore wrote an article in the Wall Street Journal with his business partner, David Blood.

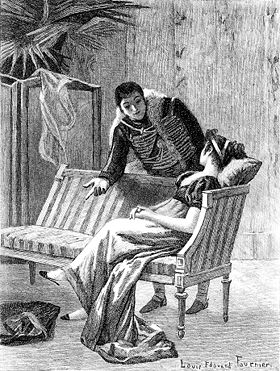

Balzac’s names

advanced into his work, the less he invented or deformed the names he used. Thus the beauty of the Balzacien name comes essentially from the weight it has on human beings, who can never change it, even when they try, like bastards, criminals, or great ladies wishing for a new personality. The bourgeois name is a true tunic of Nessus, which one never manages to completely rip off, especially in the modern French onomastic system, infinitely more binding than the practice of the Ancien Régime, entirely commanded by the father’s name. It is the sign of a civilization of writing. And everyone is obsessed with the desire for an indelible signature, in inscribing his name in the commercial, scientific, historical, or institutional circuit. The bourgeoisie of the 19th century gave itself up to a veritable onomastic debauchery, in “giving” its names to anything and everything, to a product, to streets, to discoveries, mountains, or literary prizes. When Balzac delved with both hands into the names of his neighbors in Tours for his characters’ names, all he did was anticipate this way of behaving. The procedure is the same for places: to take their names is to symbolically appropriate their substance, the best of their being.

advanced into his work, the less he invented or deformed the names he used. Thus the beauty of the Balzacien name comes essentially from the weight it has on human beings, who can never change it, even when they try, like bastards, criminals, or great ladies wishing for a new personality. The bourgeois name is a true tunic of Nessus, which one never manages to completely rip off, especially in the modern French onomastic system, infinitely more binding than the practice of the Ancien Régime, entirely commanded by the father’s name. It is the sign of a civilization of writing. And everyone is obsessed with the desire for an indelible signature, in inscribing his name in the commercial, scientific, historical, or institutional circuit. The bourgeoisie of the 19th century gave itself up to a veritable onomastic debauchery, in “giving” its names to anything and everything, to a product, to streets, to discoveries, mountains, or literary prizes. When Balzac delved with both hands into the names of his neighbors in Tours for his characters’ names, all he did was anticipate this way of behaving. The procedure is the same for places: to take their names is to symbolically appropriate their substance, the best of their being.—Nicole Mozet, La ville de province dans l’oeuvre de Balzac: l’espace romanesque : fantasme et ideologie (Paris, Societe d’edition d’enseignement superieur, 1982)

La Comédie humaine est une enorme épopée onomastique. Les noms propres sont des morceaux de corps, des morceaux de terre, de purs signifiants. Dans tout son oeuvre, Balzac nous présent des noms magiques, comme celui de Foedora ou de Z. Marcas, des noms prestigieux, comme celui de Beauséant, des noms drolatiques, comme Beaupertuys, des noms grossiers, comme Beauvisage, voire ignobles, comme Crochard ou Gaubertin….

…cette “singulière theorie sur les noms” que professait Balzac, d’après sa soeur, et qui voulait que “les noms inventés ne donnent pas la vie aux êtres imaginaires, tandis que ceux qui ont réellement été portés les douent de réalité.” Il semble effectivement que Balzac, au fur et à mesure qu’il s’avançait dans son oeuvre, ait de moins en moins inventé et déformé les noms qui’il utilisait. Aussi la beauté du nom Balzacien vient-elle essentiellement du poids que celui-ci fait peser sur les êtres, qui n’en peuvent jamais changer, même quand ils essaient, comme les bâtards, les criminels, ou les grandes dames en mal d’une nouvelle personnalité. Le nom bourgeois est un véritable tunique de Nessus, que l’on ne parvient jamais à arracher complètement, surtout dans le système onomastique français moderne, infiniment plus contraignant que la pratique de l’Ancien Régime, et entièrement commandé par le nom du père. C’est le signe d’une civilisation de l’écrit. Et chacun d’être obsédé par le désir d’une signature indélébile, en inscrivant son nom dans le circuit commercial, scientifique, historique ou institutionnel. La bourgeoisie du XIXeme siècle s’est livrée a une véritable débauche onomastique, en “donnant” ses noms à tous vents, à un produit, à des rues, à des découvertes, à des montagnes ou à des prix littéraires. Balzac n’a fait qu’anticiper sur cette façon d’agir lorsqu’il a puisé à pleines mains dans les noms de ses voisins de Tours pour les faire porter par ses personnages. Le procédé est le même quand il s’agit des lieux: prendre leurs noms, c’est s’approprier symboliquement leur substance, le meilleur de leur être.

…cette “singulière theorie sur les noms” que professait Balzac, d’après sa soeur, et qui voulait que “les noms inventés ne donnent pas la vie aux êtres imaginaires, tandis que ceux qui ont réellement été portés les douent de réalité.” Il semble effectivement que Balzac, au fur et à mesure qu’il s’avançait dans son oeuvre, ait de moins en moins inventé et déformé les noms qui’il utilisait. Aussi la beauté du nom Balzacien vient-elle essentiellement du poids que celui-ci fait peser sur les êtres, qui n’en peuvent jamais changer, même quand ils essaient, comme les bâtards, les criminels, ou les grandes dames en mal d’une nouvelle personnalité. Le nom bourgeois est un véritable tunique de Nessus, que l’on ne parvient jamais à arracher complètement, surtout dans le système onomastique français moderne, infiniment plus contraignant que la pratique de l’Ancien Régime, et entièrement commandé par le nom du père. C’est le signe d’une civilisation de l’écrit. Et chacun d’être obsédé par le désir d’une signature indélébile, en inscrivant son nom dans le circuit commercial, scientifique, historique ou institutionnel. La bourgeoisie du XIXeme siècle s’est livrée a une véritable débauche onomastique, en “donnant” ses noms à tous vents, à un produit, à des rues, à des découvertes, à des montagnes ou à des prix littéraires. Balzac n’a fait qu’anticiper sur cette façon d’agir lorsqu’il a puisé à pleines mains dans les noms de ses voisins de Tours pour les faire porter par ses personnages. Le procédé est le même quand il s’agit des lieux: prendre leurs noms, c’est s’approprier symboliquement leur substance, le meilleur de leur être.

John Gardner: To change a character’s name is to make the fictional ground shudder

As in the universe every atom has an effect, however minuscule, on every other atom, so that to pinch the fabric of Time and Space at any point is to shake the whole length and breadth of it, so in fiction every element has effect on every other, so that to change a character’s name from Jane to Cynthia is to make the fictional ground shudder under her feet.

—John Gardner (1933-1982), The Art of Fiction (1983), ch. 3

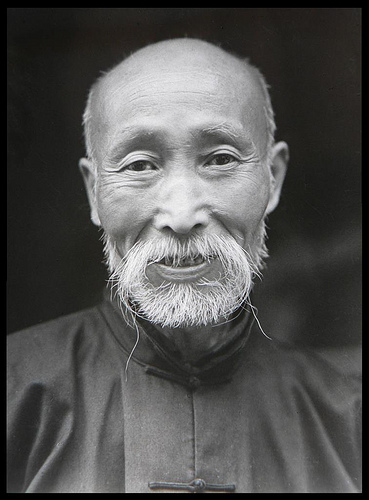

Confucius: Names must be correct

Confucius said, “Correcting names, of course!”

Zi Lu said, “Oh really! That’s far-fetched! How would you correct them?”

Confucius said, “Zi Lu, you are really barbaric. A noble man, when faced with something he does not know, tries to hide his ignorance.

“If names are not correct, then words are unfitting; if words are unfitting, then matters are not accomplished. If matters are not accomplished, then ceremony and music will not flourish. If ceremony and music do not flourish, then justice will not be evenhanded. If justice is not evenhanded, the people will be tied hand and foot. That is why the noble man must use names that can be spoken, and words that can become deeds. The noble man never speaks carelessly, that’s all there is to it.”

—From the Analects of Confucius (551-579 B.C.) (論語), 13:3 (Zi Lu 子路)

子路曰:“衛君待子而為政,子將奚先?”子曰:“必也正名乎!”子路曰:“有是哉,子之迂也!奚其正?”子曰:“野哉由也!君子於其所不知,蓋闕如也。名不正,則言不順;言不順,則事不成;事不成,則禮樂不興;禮樂不興,則刑罰不中;刑罰不中,則民無所措手足。故君子名之必可言也,言之必可行也。君子於其言,無所苟而已矣。”

Halldór Laxness: Fatherless children in Iceland are called Hansson

Then one day, so I have been told, it happened that a young woman arrived at the place from somewhere in the west; or north; or perhaps even east. This woman was on her way to America, abandoned and destitute, fleeing from those who ruled over Iceland. I have heard that her passage had been paid for by the Mormons, and indeed I know for a fact that among them are to be found some of the finest people in America. But anyway, without further ado, this woman I mentioned gave birth to a baby while she was staying at Brekkukot waiting for her ship. And when she had been delivered of the child she looked at her newborn son and said, “This boy is to be called Álfur.”

“I would be inclined to name him Grímur,” said my grandmother.

“Then we shall call him Álfgrímur,” said my mother.

And so the only thing this woman ever gave me, apart from a body and soul, was this name: Álfgrímur. Like all fatherless children in Iceland I was called Hansson– literally, “His-son.”

—From The Fish Can Sing (Brekkukotsannáll)(1957), by Halldór Laxness (1902-1998), translated by Magnus Magnusson (1929-2007)

About names in the Bible

For now have I chosen and sanctified this house, that my NAME may be there for ever: and mine eyes and mine heart shall be there perpetually.

Mine enemies speak evil of me, When shall he die, and his NAME perish?

I will make thy NAME to be remembered in all generations: therefore shall the people praise thee for ever and ever.

Let his posterity be cut off; [and] in the generation following let their NAME be blotted out.

A [good] NAME [is] rather to be chosen than great riches, [and] loving favour rather than silver and gold.

A good NAME [is] better than precious ointment; and the day of death than the day of one’s birth.

And it came to pass on the morrow, that Pashur brought forth Jeremiah out of the stocks. Then said Jeremiah unto him, The LORD hath not called thy NAME Pashur, but Magormissabib.

And he asked him, What [is] thy NAME? And he answered, saying, My NAME [is] Legion: for we are many.

Dao De Jing: The name that can be named is not the eternal name

The name that can be named is not the eternal name. The nameless is at the beginning of heaven and earth; the named is the mother of all things.

— The Dao De Jing (道德經), said to be written by Laozi (老子), the Old Master

名可名非常名。無名天地之始;有名萬物之母。